ORGANIC MOLECULAR CHEMISTRY WITH GAS CHROMATOGRAPHY-MASS SPECTROMETRY IN GEORGE STUBBS’ INHERITANCE PORTRAIT OF JOSEPH BANKS

Khwan PHUSRISOM1,*, Aganis SUNTHINAK2, Natcha THONGPOONPHATTANAKUL3

- Baan Dong Bang Museum, 298 M15 Baan Dong Bang, Hua Na Kham, Yang Talat, Kalasin, 46120 Thailand

- Research Instrument Centre, Khon Kaen University, 123 M16, Mittraphap Rd, Muang Khon Kaen, 40002 Thailand

- Faculty of Fine and Applied Arts, Khon Kaen University, 123 M16, Mittraphap Rd, Muang Khon Kaen, 40002 Thailand

*Corresponding author: khwanphusrisom@gmail.com

Abstract. This study is part of a programme investigating the 1764 Inheritance Portrait of Joseph Banks by George Stubbs. Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry was carried out with modern high-performance equipment and software on a sub-rebate paint sample. Three different solvents were used, namely acetone, methanol, and ethyl acetate, having broader potential for determining chromatogram peaks than earlier published research on Stubbs’ works. The determined fatty acids were typical for those dissolved from dried, oxidised Linseed oil, used both in paint ground and varnish at the time. The incorporation of Silicon into one fatty acid may have originated from Linseed oil per se, or have been a dynamic inclusion in the oxidation process, from earth Silicon associated with pigments, binding into drying Linseed oil from the paint ground. The absence of lignoceric acid, which does not oxidise in air like Linseed oil fatty acids, firmly excluded the use of beeswax in this paint ground. As no evidence was found for lipids typical to oils other than oxidized Linseed, the date of Stubbs later modifying drying agents and the date of Banks’ inheritance are closely consistent. It is envisaged that these organic molecule determinations using three different solvents will help future comparative research.

Key words: Organic molecular chemistry; gas chromatography-mass spectrometry; multiple solvents; linseed oil; George Stubbs; Joseph Banks

Introduction

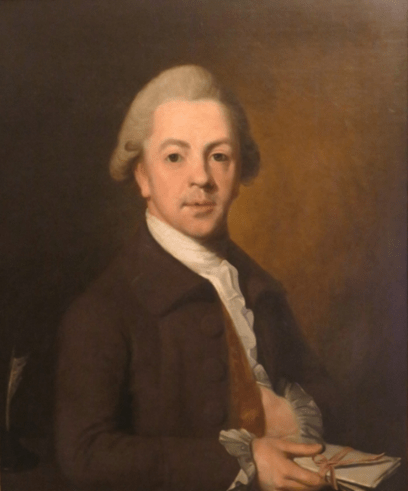

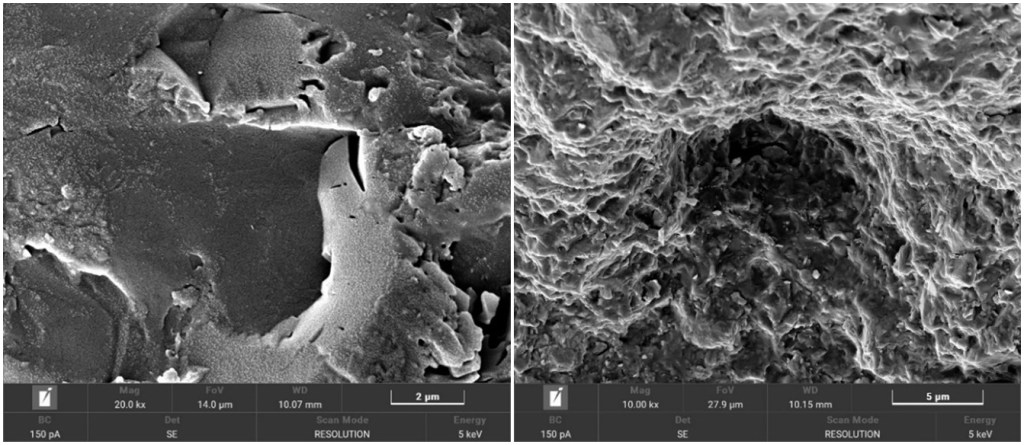

While the 1980’s saw a flurry of technical research on the paintings of George Stubbs, this has declined in recent years, but not for want of great scientific and historic importance. In 1764, George Stubbs painted Joseph Banks (Fig.1.) on his inheritance [1]. As well as symbolizing Banks’ imminent botanical exploration and co-founding modern Australia, this painting is important for historians, art material scientists, conservators and authenticators as a rare example of an oil on canvas personal portrait signed by Stubbs. By then he had matured artistically and had already created his other masterpieces of Whistlejacket and several horse and lion paintings. Previous research of the index portrait with scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and atomic scatter[2]revealed Stubbs’ use of well-plasticised Linseed oil in varnish (Fig. 2A) and paint ground (Fig. 2B), underneath part-burnt restoration varnish. The Tescan-3 micrographs illustrating these here in natural colourising have not been previously published. Atomic composition of pigments had revealed Carbon and Calcium Carbonate from Black Ivory and Iron from Burnt Sienna, besides Carbon and Oxygen from varnish. Small quantities of determined Nitrogen, Aluminium and Silicon were assumed to be soil trace elements.

This study aimed to determine the organic molecular chemistry of a single sample comprising varnish and paint ground taken from the index portrait. The importance of this was to establish a database for future comparison in the research of other potential contemporaneous portraits by Stubbs. These can be unsigned and have therefore sometimes been overlooked. Secondarily, evidence was sought to exclude fatty acids atypical for Linseed oil oxidation, given Stubbs’ demonstrable later addition of waxes for paint ground flexibility from 1767 and his drying oil modification from 1783 [3]. These practices of his were confirmed in a study of ten later Stubbs paintings [4]. In Stubbs’ Hambletonian, Rubbing Down, from his late phase, painted in 1800, GC-MS demonstrated Stubbs’ use of pine resin with components of Methyl dihydroabietate and 7-oxodehydroabietate. His beeswax separated as chromatographic long chain fatty acids representing overwhelming hexadecanoate, then termed palmitate when investigated [5].Knowledge of thelipids of Stubbs’ works is crucial for restorers to avoid damage by heat or inappropriate solvents. In turn, the potential datability of Stubbs’ works from his techniques, means that an extra strand of scientific dating evidence can inform historical research.

A) Plasticised varnish surface B) paint pigments in dried oil with no visible wax globules.

Materials and Methods

Sampling

A tiny paint fragment was taken from the top left edge of Stubbs’ dark brown background from an area behind the rebate of the frame.

Instrumentation and chromatographic conditions

Determination of a crude paint sample extract was performed by 300 °C injection, Agilent gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS), outsourced to Khon Kaen University, Thailand, while the painting remained in the UK. The separation was carried out under the conditions in table 1. The splitless injection mode used refers to the split vent being closed and left closed before and during the injection. As there is no split flow, the total flow is set at a dramatically reduced flow rate. Total Ion Chromatograms (TIC) acquisition mode summed up intensities of all mass spectral peaks belonging to the same scan.

Table 1. GC-MS conditions.

| GC system: | Agilent 8890 gas chromatograph (Agilent Technology, USA) |

| Mass spectrometer: | 5977B mass spectrometer (Agilent Technology, USA) |

| Automatic liquid sampler: | 7693A automatic liquid sampler (Agilent Technology, USA) |

| Instrument control and data acquisition: | MassHunter Software (Agilent Technology, USA) |

| Column: | DB-5ms GC Column, 30 m, 0.25 mm, 0.25 µm (Agilent Technology, USA) |

| Column oven temperature: | 80 °C (2 min) —> 20 °C/min, 220 °C –> 4 °C/min, 300 °C (1 min) |

| Run Time: | 30 min |

| Injection Mode: | Splitless |

| Injection Volume: | 1 µL |

| Injection temperature: | 300 °C |

| Flow: | 1.2 mL/min |

| Acquisition Mode: | TIC mode |

Solvent extraction from the paint sample for analysis

A paint sample of 0.5 mg was mixed with 100 µL of each of three different 100% pure solvents for extraction, namely acetone, methanol, and ethyl acetate. The mixture was vortexed for 1 minute and filtered by a 0.22 micron membrane filter before analysis with GC-MS.

Results and Discussions

Acetone solvent

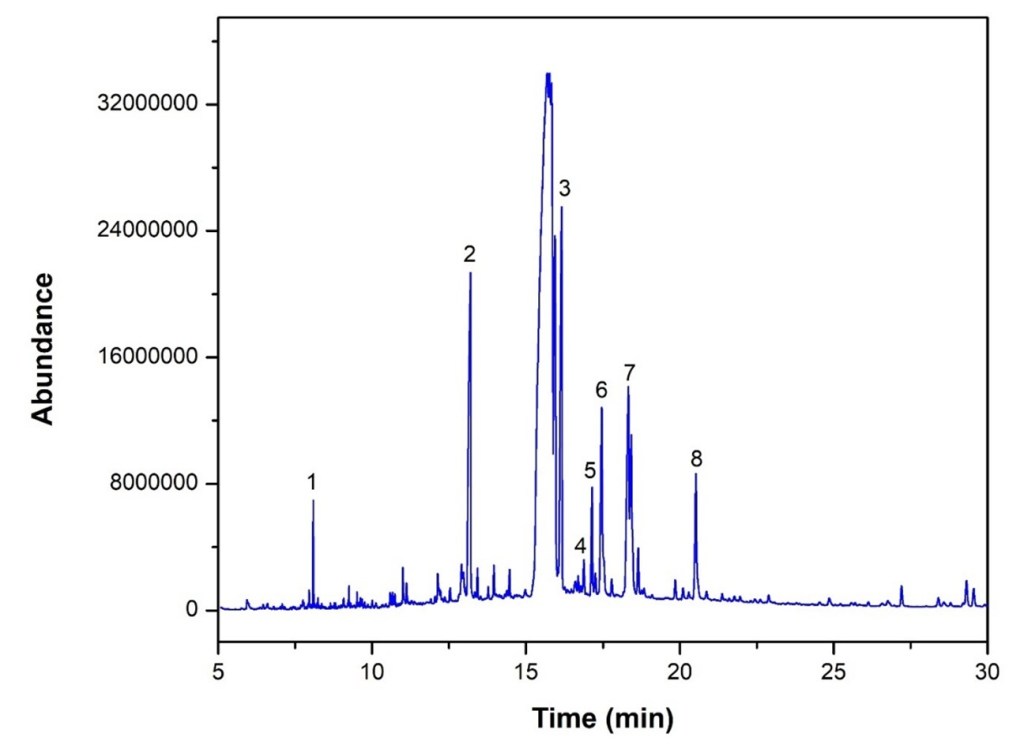

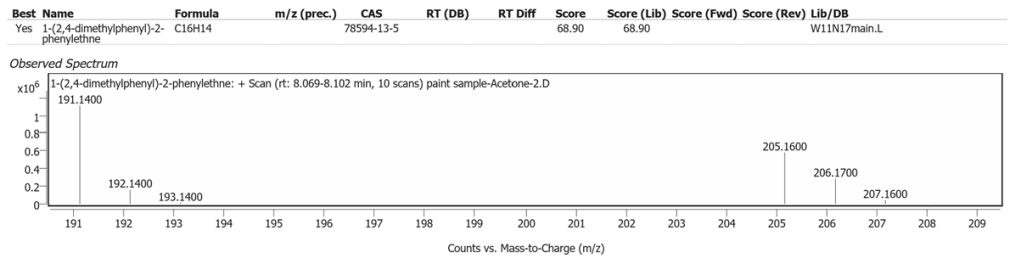

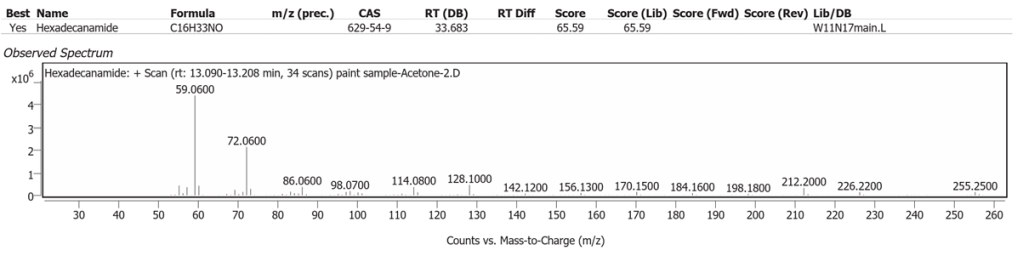

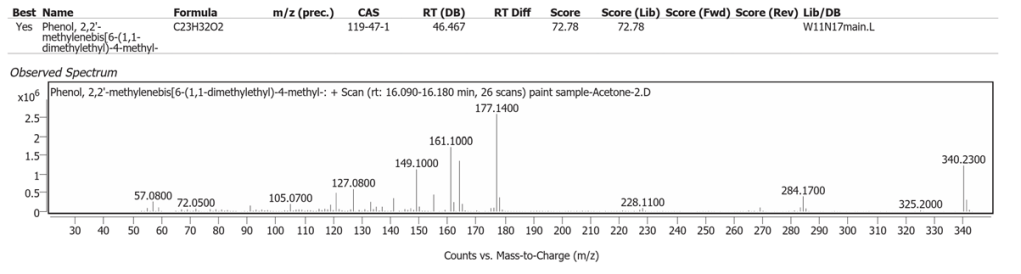

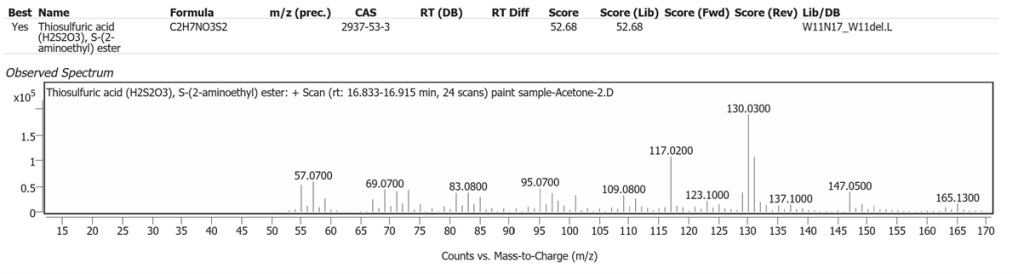

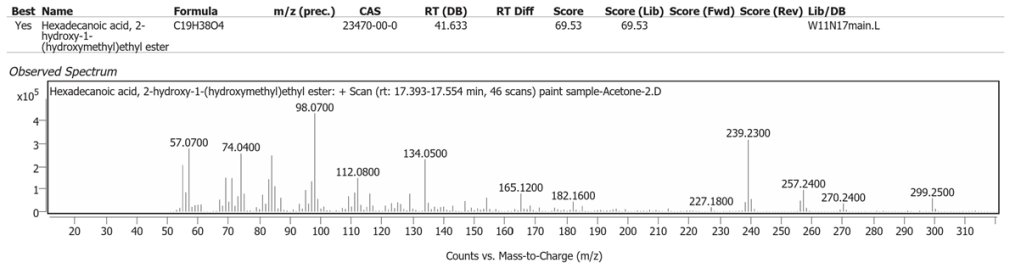

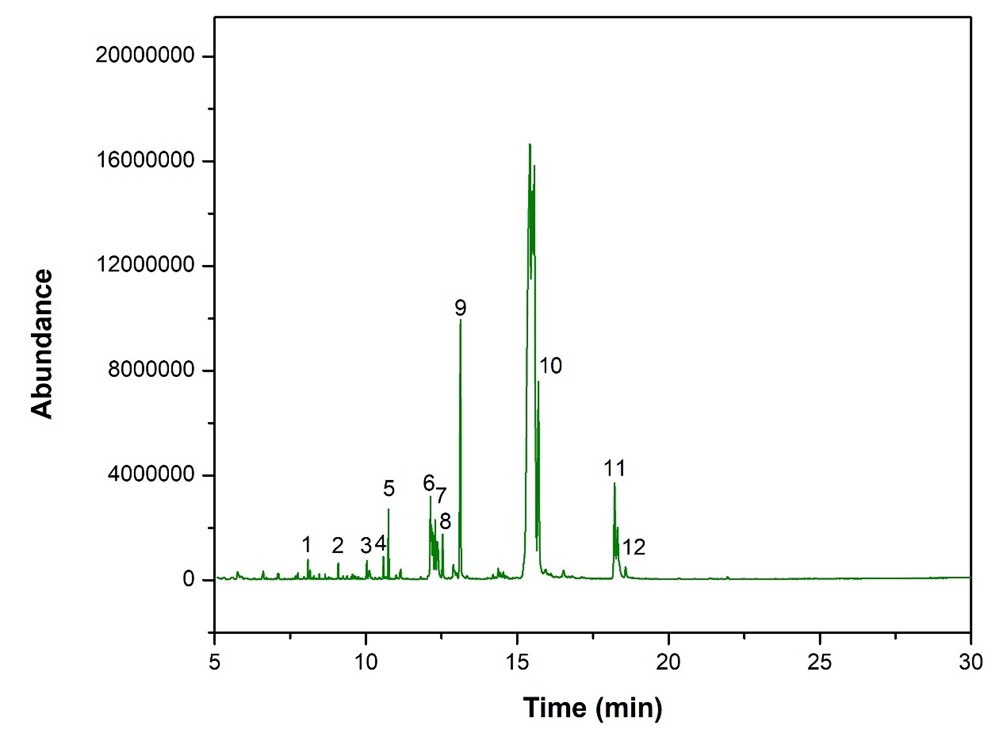

GC-MS of the acetone-extracted material revealed eight fatty acid peaks consistent with Linseed oil, reported with retention times and scores in Table 2.

Table 2. Determination of crude paint sample, acetone extract.

| No. | Retention time mins | Name | Formula | Score |

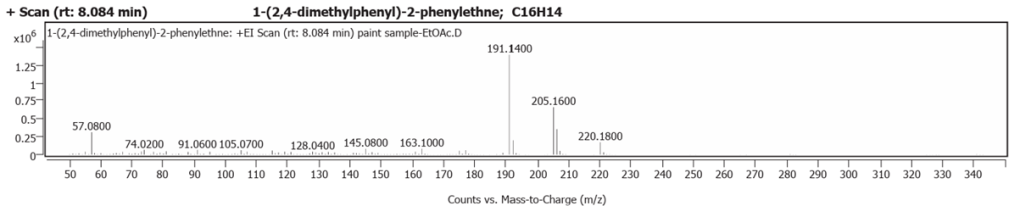

| 1 | 8.084 | 1-(2,4-dimethylphenyl)-2-phenylethne | C16H14 | 68.90 |

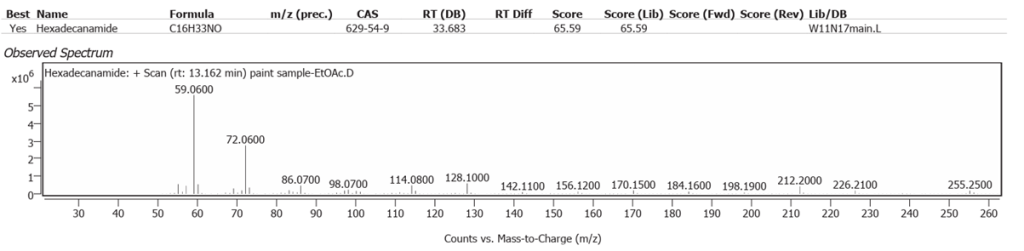

| 2 | 13.198 | Hexadecanamide | C16H33NO | 65.59 |

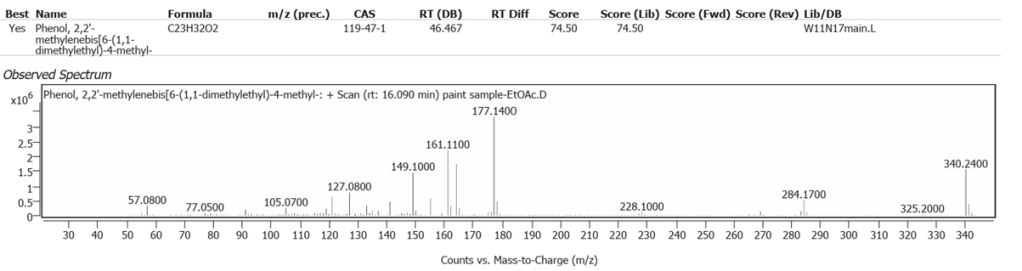

| 3 | 16.158 | Phenol,2,2′-methylenebis[6-(1,1-dimethylethyl)-4-methyl | C23H32O2 | 72.78 |

| 4 | 16.868 | Thiosulfuric acid(H2S2O3), S-(2 aminoethyl) ester | C2H7NO3S2 | 52.68 |

| 5 | 17.145 | 1,5,9-Decatriyne-5,6-13C2 | C10H10 | 49.44 |

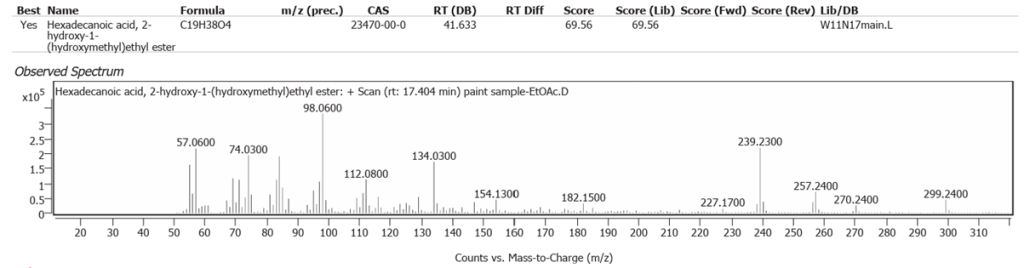

| 6 | 17.465 | Hexadecanoic acid, 2-hydroxy-1-(hydroxymethyl)ethyl ester | C19H38O4 | 69.53 |

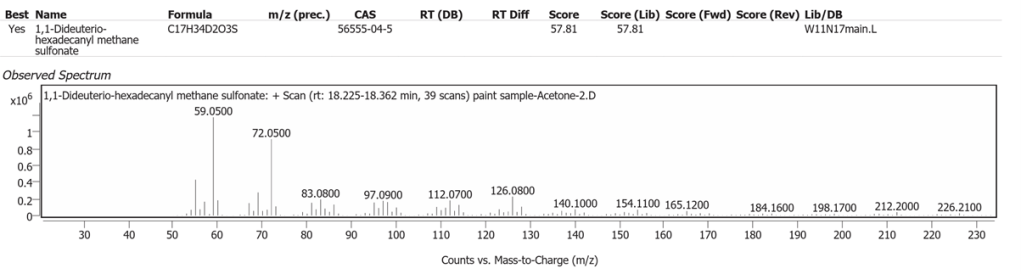

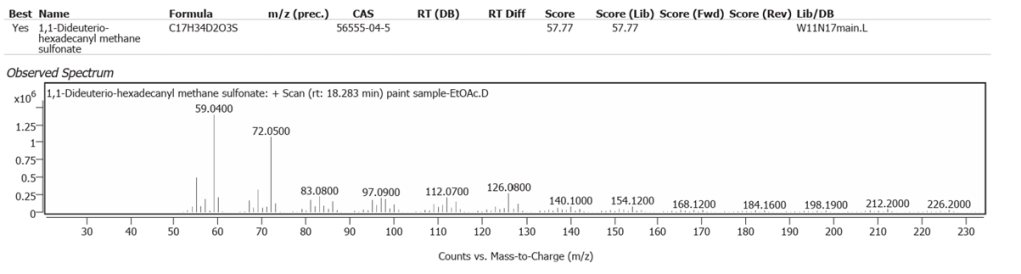

| 7 | 18.329 | 1,1-Dideuterio-hexadecanyl methane sulfonate | C17H34D2O3S | 57.81 |

| 8 | 20.555 | Octadecanoic acid, 2,3-dihydroxypropyl ester | C21H42O4 | 67.13 |

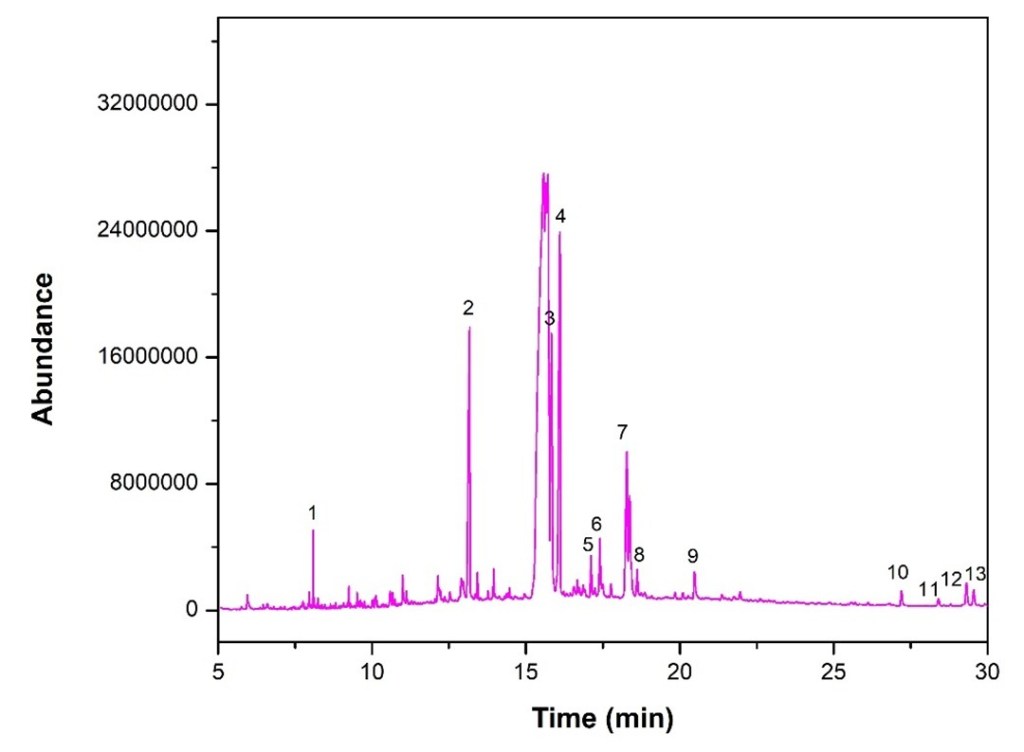

The abundances of the eight peaks arising in time sequence are shown in figure 3.

The spectrum analyses for each peak are shown in figures 4 to 11.

Methanol solvent

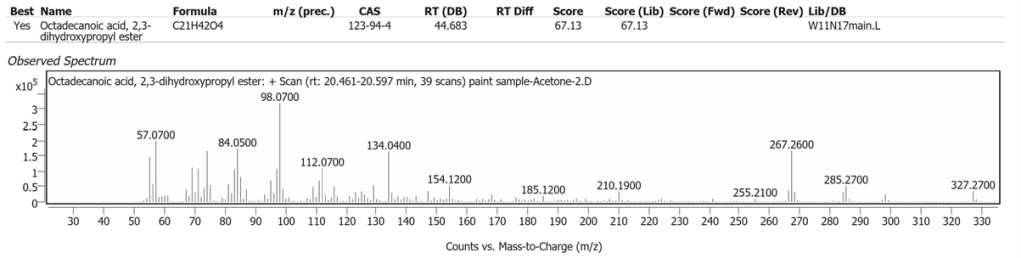

GC-MS of the methanol-extracted material revealed twelve fatty acid peaks consistent with Linseed oil, reported with retention times and scores in Table 3.

Table 3. Determination of crude paint sample, methanol extract.

| No. | Retention time | Name | Formula | Score |

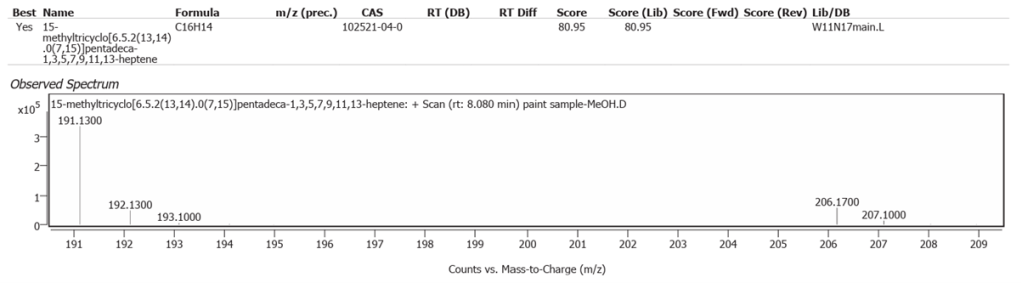

| 1 | 8.080 | 15 methyltricyclo[6.5.2(13,14).0(7,15)]pentadeca 1,3,5,7,9,11,13-heptene | C16H14 | 80.95 |

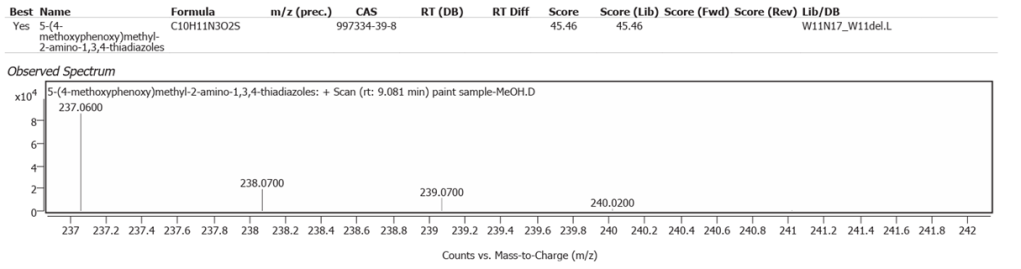

| 2 | 9.081 | 5-(4-methoxyphenoxy)methyl-2-amino-1,3,4-thiadiazoles | C10H11N3O2S | 45.46 |

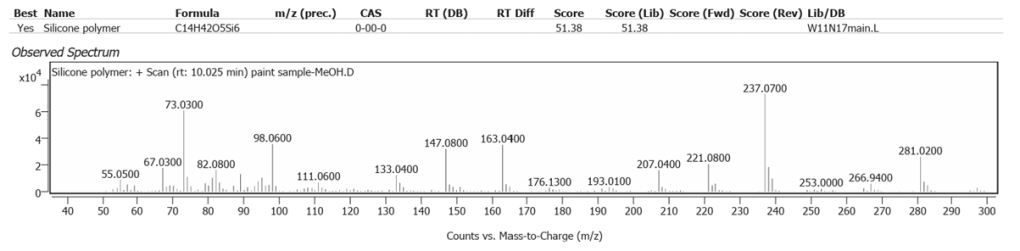

| 3 | 10.025 | Silicone polymer | C14H42O5Si6 | 51.38 |

| 4 | 10.585 | Heptadecene-(8)-carbonic acid-(1) | C18H34O2 | 64.00 |

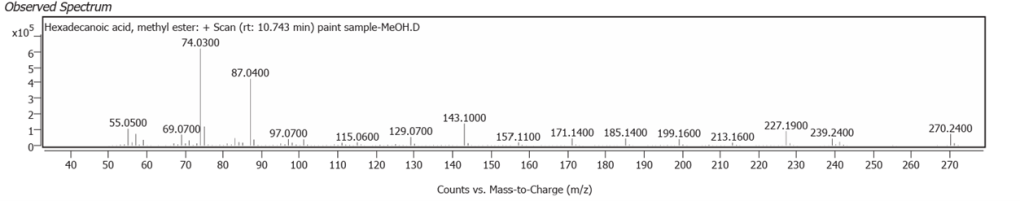

| 5 | 10.743 | Hexadecanoic acid, methyl ester | C17H34O2 | 70.96 |

| 6 | 12.135 | 9-Octadecenenitrile | C18H33N | 58.90 |

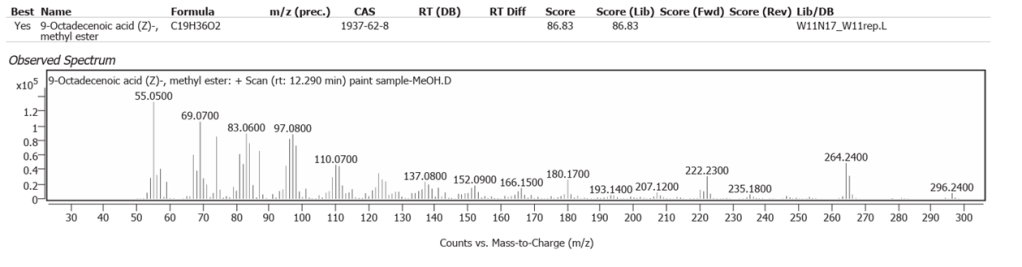

| 7 | 12.290 | 9-Octadecenoic acid (Z)-, methyl ester | C19H36O2 | 86.83 |

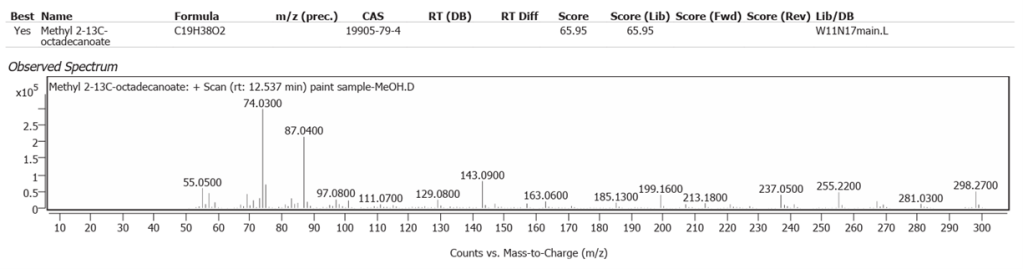

| 8 | 12.537 | Methyl 2-13C octadecanoate | C19H38O2 | 65.95 |

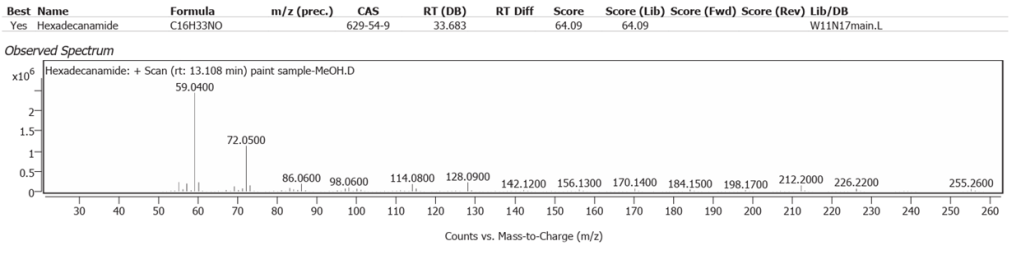

| 9 | 13.108 | Hexadecanamide | C16H33NO | 64.09 |

| 10 | 15.703 | Octadecanamide | C18H37NO | 57.15 |

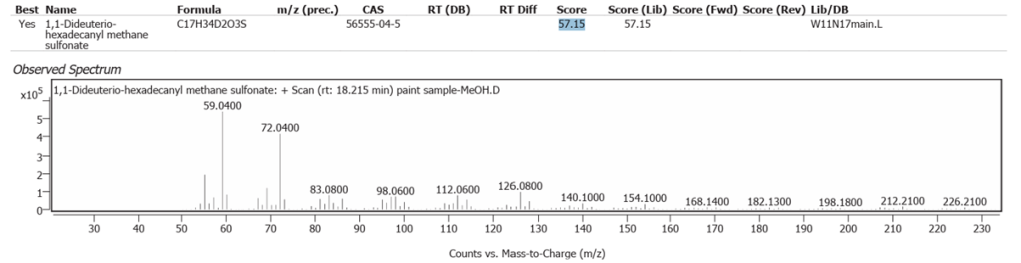

| 11 | 18.215 | 1,1-Dideuterio-hexadecanyl methane sulfonate | C17H34D2O3S | 57.15 |

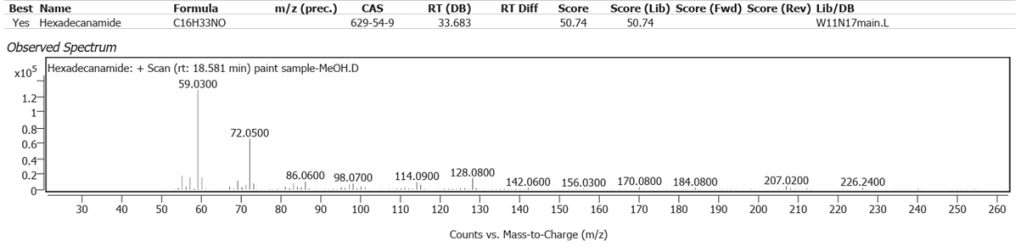

| 12 | 18.581 | Hexadecanamide | C16H33NO | 50.74 |

The abundances of the twelve peaks arising in time sequence are shown in figure 12.

The spectrum analyses for each peak are shown in figures13 to 24.

pentadeca1,3,5,7,9,11,13-heptene.

Ethyl acetate solvent

GC-MS of the ethyl acetate-extracted material revealed eleven fatty acid peaks consistent with Linseed oil and two apparent artefactual miscellanies. These are reported with their retention times and scores in Table 4.

Table 4. Determination of crude paint sample, ethyl acetate extract

| No. | Retention time | Name | Formula | Score |

| 1 | 8.084 | 1-(2,4-dimethylphenyl)-2-phenylethne | C16H14 | 69.44 |

| 2 | 13.162 | Hexadecanamide | C16H33NO | 65.59 |

| 3 | 15.835 | Octadecanamide | C18H37NO | 57.18 |

| 4 | 16.090 | Phenol,2,2′-methylenebis[6-(1,1-dimethylethyl)-4-methyl | C23H32O2 | 74.50 |

| 5 | 17.120 | 1,5,9-Decatriyne-5,6-13C2 | C10H10 | 47.88 |

| 6 | 17.404 | Hexadecanoic acid, 2-hydroxy-1-(hydroxymethyl)ethyl ester | C19H38O4 | 69.56 |

| 7 | 18.283 | 1,1-Dideuterio-hexadecanyl methane sulfonate | C17H34D2O3S | 57.77 |

| 8 | 18.609 | Dihydromyrcenol | C10H20O | 52.63 |

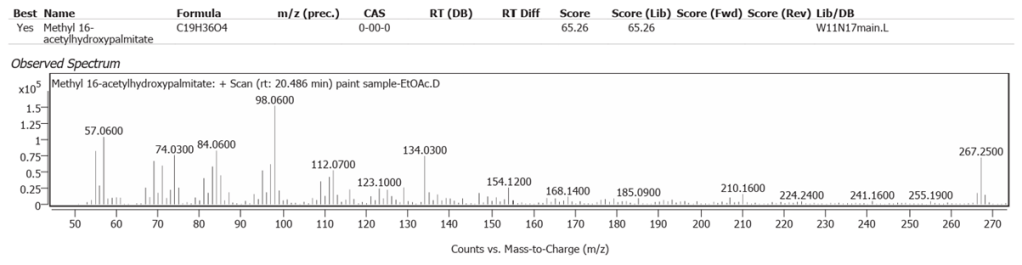

| 9 | 20.486 | Methyl 16-acetylhydroxypalmitate | C19H36O4 | 65.26 |

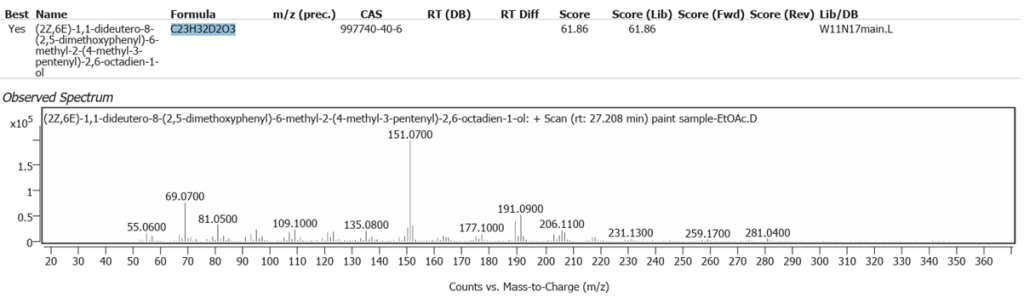

| 10 | 27.208 | (2Z,6E)-1,1-dideutero-8-(2,5-dimethoxyphenyl)-6-methyl-2-(4-methyl-3-pentenyl)-2,6-octadien-1-ol | C23H32D2O3 | 61.86 |

| 11 | 28.403 | Solanesol | C45H74O | 59.67 |

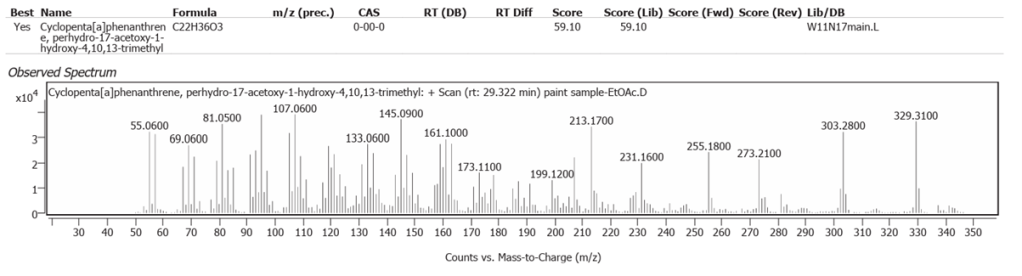

| 12 | 29.322 | Cyclopenta[a]phenanthrene, perhydro-17-acetoxy-1-hydroxy-4,10,13-trimethyl | C22H36O3 | 59.10 |

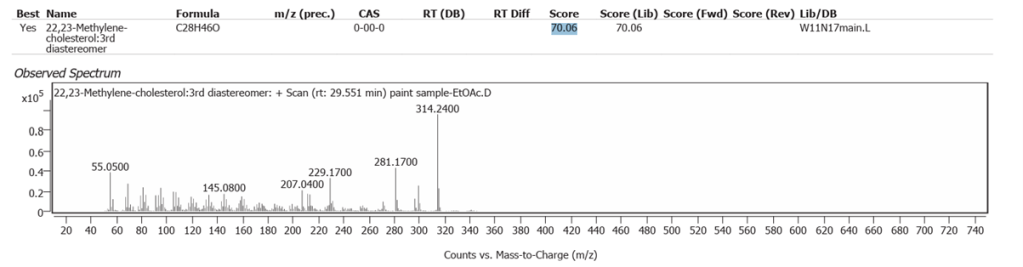

| 13 | 29.551 | 22,23-Methylene-cholesterol:3rd diastereomer | C28H46O | 70.06 |

The abundances of the thirteen peaks arising in time sequence are shown in figure 25.

The spectrum analyses for each peak are shown in figures 26 to 38.

Interpreting these findings proved novel and interesting. It is notable in these results that with advanced equipment and three different solvents, different profiles arose with each. This emphasises the importance of galleries and universities doing scientific research on paint and varnish with the best, standardised techniques for organic compound analysis [6].

Linseed oil naturally has variable composition and oxidises to different molecules in processes still not fully understood.One source of variability is that oils synthesized by plants are not only determined by their genetics, but also by location and climate [7]. Octadecanoic acid (Stearic acid) and Hexadecanoic acid (Palmitic acid), are the two fatty acids of Linseed oil which may modify but do not denature on oxidative polymerisation. They comprise the highest peaks here, along with their decanamides, which are the carboxylic acid amides derived from amines of the source flax plant, Linum usitatissimum. The full range of compounds determined in this study are largely the oxidized derivatives of Octadecanoate (Palmitate) and Hexadecanoate (Stearate) from Linseed oil. Hexadecanamide was detected with all three solvents.

The silicone polymer Tetradecamethylhexasiloxane C14H42O5Si6 was determined. It occurs naturally in Basil oil. Whilst this oil is not used in art materials, Basil oil is chemically similar to Linseed oil [8]. Linseed oil as the origin of Silicon is an alternative explanation to an earth trace pigment source of Silicon in the sample; in other words a natural silicon polymer, rather than a dynamic inclusion in the oxidation process of earth silicon, with pigments binding into Linseed oil in the paint ground as it dried.

The determination of Nitrogen in the previous atomic scatter study was assumed to be from soil in Burnt Sienna, but the plant amides clearly show the Linseed oil as a source, with or without some soil origin.

Over 95% of soil Sulfur is organic from plants [9]. It is more likely that the sulfonates determined were Linseed oil derivatives and not from soil/ground-derived burnt Sienna pigment.

Significant compounds excluded

These findings excluded the fatty acid Lignoceric acid which is characteristic of beeswax and occurs in significant quantity with it. Beeswax contains all of the five principle fatty acids of Linseed oil with two to threefold variation in the quantity of each, depending on the bees’ colony. Beeswax is, of course, plant-derived from the flowers from where the worker bees pick it up. Like Linseed oil, the determined organic chemistry has environmental variables, besides plant genetics [10]. Lignoceric acid oxidises biochemically within cells but, importantly, appears to be stable in air [11].Its absence in the sample substantiates Stubbs’ known use of Linseed oil alone at the time of the painting. That is helpfully consistent with the date of the painting, shortly before Stubbs added waxes to his paint ground. Beeswax slows oil drying. It can cause more smearing, despite the potential to reduce cracking. Stubbs’ subsequent use suggests he was trying to improve his paint flexibility

Most modern oil paint manufacturers use only Castor wax in all their paint, which is hydrogenated Castor oil. It was not used in the eighteenth century. Nickel is used to catalyse faster hydrogenation of Castor wax in modern oil paint. Its presence on SEM-EDRS is therefore important in authentication, implying modern paint. Notably, the previous SEM atomic scatter had detected no Nickel at all, implying that these GC-MS organic findings reflect historic oil without it.

There was no reason to expect pine resin derivatives, but the absence of Methyl dihydroabietate and 7-oxodehydroabietate does substantiate the existing evidence of Stubbs using the resin after the year 1800.

Miscellaneous compounds with ethyl acetate solvent

Methylene-cholesterol and Cyclopenta[a]phenanthrene, perhydro-17-acetoxy-1-hydroxy-4,10,13-trimethyl, both of which were determined in low abundance, probably represent molecules in plant steroid pathways in the flax-derived Linseed oil.

The Solanesol has arisen from tobacco smoke at some phase in the picture’s history. It is not known if Stubbs or Banks themselves smoked.

Phenol,2,2′-methylenebis[6-(1,1-dimethylethyl)-4-methyl is a modern materials antioxidant and we suspect that this is a contaminant from storage, such as polystyrene packaging while the painting was out of its frame even though it was covered with long fibre paper. Another explanation is the clear plastic petri dish used in the sampling process. This compound does not match any historic or modern art material component.

Deuterium isotope determination where it arose here in fatty acids derived from all three solvents is from hexadecanoate and derivative analytical processing incorporation, and not, of course, from historic or even modern paint and varnish oil.

Dating, technical progress and further research

Van den Berg’s seminal atlas of Linseed oil chromatogram determinants used Methanol solvent alone and studied Linseed oil specifically incorporating lead drying agent [12]. The findings in this study are from three solvent sample cells with no lead in the general paint ground. Lead was not significant in the paint ground of the index painting, as SEM atomic scatter of Banks by Stubbs only detected lead in a single particle and none on wide field paint ground or wide field varnish analysis. Van den Berg’s determinants showed no amides and sulfonates. Nevertheless, both data sets are consistent with Linseed oil alone. The reasons behind the variation are doubtless complex as with any analysis of Linseed oil and need to be the subject of future research. Van den Berg’s data arose from higher, not lower injection temperatures, where more denaturing not less would be expected. Ageing of modern oil paints under high humidity increases the formation of dicarboxylic acids and hydrolysis, followed by evaporation of free fatty acids. There is scope to replicate this work with historic art oil which might shed light on the potential impact of environmental humidity variability in GC-MS findings [13]. Such knowledge is desirable in the interpretation of findings across different studies with GC-MS.

From appearance alone, Banks is considerably more youthful in the index painting than in his portrait finished by Joshua Reynolds in 1773. He is thinner faced than in his picture exhibited by Benjamin West exhibited the same year. Stubbs was unlikely to have used anything other than Linseed oil for ground and varnish in the index portrait, from the known history of his materials which he modified from Linseed oil alone after 1767. The remote possibility of Stubbs having resurrected historic Walnut oil is excluded, as it yields minimal octa- and hexadecanoate [14], unlike these results with all three solvents. The chance of Stubbs picking up the idea of nut oil use when studying in Italy in 1754 would have been slim anyway, as it was already obsolete there, despite its use in the later renaissance lasting long beyond Northern European practice.

One source of variability in GC-MS determination of fatty acids is the complexity of molecular change in pyrolysis, including potential fragmentation, double bond isomer formation and acid methylation [15].From the variability of study results with GC-MS on Linseed oil, this has to be born in mind in comparative research. Whilst you cannot completely match or exclude an artist’s technique with another painting from detailed determination of GC-MS Linseed oil-derived fatty acid variability alone, in this study the following conclusions are hard to refute in terms of what they represent and confirm in context. These findings do exclude important later alternative techniques in Stubbs’ case and assist dating confirmation.

Conclusions

GC-MS determined Hexadecanoate and Octadecenoate (formerly named Stearate and Palmitate respectively), and their derivatives, typical of the oxidation of Linseed oil in paint ground and varnish. The findings are entirely consistent with the date of Joseph Banks’ inheritance of 1764 shown in the portrait, given Stubbs’ later modification of his oil very shortly afterwards in 1767. Multiple pure solvents of acetone, methanol and ethyl acetate have yielded broader determined organic compound results than existing literature analysing Stubbs samples. The presence of sulfonates and amides in this study may be attributable to more sensitive detection from refined equipment and methods than in previous research. A silicon triglyceride may represent dynamic chemistry in the paint ground itself or a novel Linseed oil compound per se. These specifics of determined organic chemistry from GC-MS are the most comprehensive and up to date on Stubbs’ phase of early, fully-formed master painting. Regardless of the potential variability with Linseed oil findings, these results would be more likely to be replicated with the same technique and equipment for the same material, which we would advocate. The organic compounds determined here are comparators for future important research on Stubbs with this newly-applied, broad armamentarium of solvents in modern GC-MS.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful indeed to Khon Kaen University (KKU), Thailand, for advanced laboratory services. Particular thanks go to all who selflessly assisted from the KKU Department of Chemistry in the Faculty of Science for GC-MS and the KKU Electron Microscopy Unit in the Department of Structural Engineering, to Agilent Technologies Inc., and Prof Dr S D Martin for his advice.

References

[1] Martin S, Jones A. Anatomy and Psychology in George Stubbs’ Portrait of Joseph Banks. Hektoen International Journal of Medical Humanities. Fall, 2023.

[2] Sunthinak A, Phusrisom K, Thongpoonphattanakul. Assessment of George Stubbs’ Portrait of Joseph Banks. International Journal of Conservation Science. 16:1, 2025, 3-20.

[3] R Shepherd. Stubbs: a conservator’s view, in George Stubbs, 1724-1806. J Egerton, Intro. Tate Gallery, London, 1985.

[4] J Mills, R White. The Mediums used by George Stubbs: Some Further Studies. National Gallery Technical Bulletin. Volume 9, ed. A Roy, The National Gallery, London, 1985.

[5] J S Mills, R White. The Organic Chemistry of Museum Objects. 2nd Edition. Routledge, Abingdon and New York, 2011.

[6] Van den Berg J D J. Analytical chemical studies on traditional linseed oil paints. Thesis, externally prepared, Universiteit van Amsterdam. 2002. Atlas of GC-MS 70 eV for oil derived fatty acids in aged oil paint. p 235. Also reprinted and discussed in: J. Anal. Appl. Pyrol., 61, 1–2, van den Berg and Boon, 19, 2001.

[7] Eslahi H, Fahimi N, Sardarian A. Chemical Composition of Essential Oils. In: Essential Oils in Food Processing. Chemistry, Safety and Applications. Ed. Hashemi et al. Wiley-Blackwell, Hoboken and Oxford, October 2017, pp119-171. DOI:10.1002/9781119149392.ch4

[8] Kashere M A, Aliyu M, Sabo M, Tijjani A. Determination of phytochemical constituents in African Wild Basil (Ocimum basilicum L.) Whole plant powders for insect pest control. International Journal of Agricultural Research and Biotechnology. Nov 2022, Vol 11, no 1. https://www.hummingbirdpubng.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/TIJARBT_Vol11_No1_Nov_2022-5.pdf

[9] Jacinta Gahan, Achim Schmalenberger. The role of bacteria and mycorrhiza in plant sulfur supply. Front Plant Sci. 2014; 5: 723. Published online 2014 Dec 16. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2014.00723 PMCID: PMC4267179 PMID: 25566295

[10] Buchwald R, Breed M D, Bjostad L, Bruce E. Hibbard B E, Greenberg AR. The role of fatty acids in the mechanical properties of beeswax. Apidologie. Volume 40, Number 5, September-October 2009. Pp 585 – 594. ttps://doi.org/10.1051/apido/2009035

[11] Buchwald et al, op cit.

[12] Van den Berg, Op cit, and summarized in: Eds. Maria Perla Colombini, Francesca Modugno. Organic Mass Spectrometry in Art and Archaeology. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, Chichester, 2009.

[13] Francesca Modugno, Fabiana Di Gianvincenzo, Ilaria Degano, Inez Dorothé van der Werf, Ilaria Bonaduce & Klaas Jan van den Berg. On the influence of relative humidity on the oxidation and hydrolysis of fresh and aged oil paints. Nature: Scientific Reports, volume 9, Article number: 5533 (2019). https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-019-41893-9

[14] Ozcan, Mehmet. Some Nutritional Characteristics of Fruit and Oil of Walnut (Juglans regia L.) Growing in Turkey. I J Chem and Chem Eng, Vol 28, 2009/03/01, pp 57 – 62.

[15] Bonaduce I, Andreotti A. Chapter: Py-GC-MS of organic paint binders. In: Eds. Maria Perla Colombini, Francesca Modugno. Organic Mass Spectrometry in Art and Archaeology. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, Chichester, 2009, pp. 303-326.